In the stock market, the start of this year continued the theme of ’US exceptionalism’. That’s the belief that the US is different from other nations and, for example, that its stock market has greater potential than other markets.

However, Trump’s tariff agenda and other policies shifted that belief somewhat. Continued volatility from the US appears likely, was the case during the confusion about tariffs. Trump’s behaviour, saying one thing and then changing his mind, appears to be a feature of his administration, not a bug. That’s something we may all need to consider more carefully from now on, before judging Trump’s comments.

For a while, Trump’s policies shifted investors away from investing in US assets and rotated them into other regions. In that respect, the UK has had a relatively good year. The FTSE-100 index was up 11.7% in the first seven months of the year. It outperformed the US market helped by the uncertain international environment, by the UK market’s relatively cheap valuation and by its more defensive, less volatile nature.

Recently, however, as the dust settled and President Trump watered down his tariffs, the UK’s stock market performance softened. In recent weeks, there has been a shift back from defensive behaviour to cyclical regions such as the EU or the US. This also means that US valuations look stretched once again.

Source: Bank of England

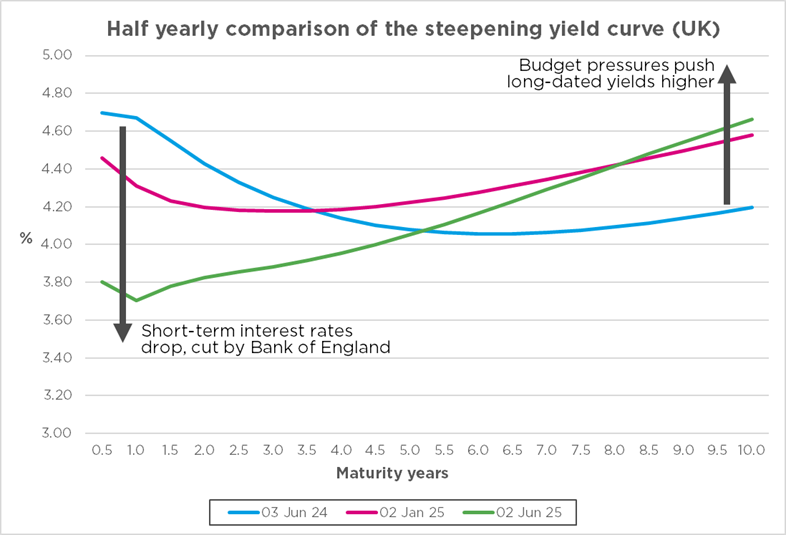

Bond markets, meanwhile, are seeing higher yields on long-term bonds, relative to short-term yields, particularly in the US and the UK. As figure 1 shows, the UK yield curve is much steeper now than at the year’s start. This is partly due to a spillover from US policy, and partly due to the UK government’s own budget issues.

Key is that a steeper yield curve makes the government’s long-term borrowing more expensive. Relief could come if the Bank of England continues to lower short-term rates as it did, for the third time this year, on 7 August. More cuts may help reduce borrowing costs across the curve.

Mansion House Accord: the potential rewards

UK government policies also affect the market outlook. The Mansion House Accord, for example, has seen 17 of the UK’s largest pension providers pledge to invest at least 10% of their defined contribution (DC) default funds in private markets by 2030, with 5% of the total allocated to the UK.

This initiative started off as voluntary but could become compulsory. On one hand, it encourages investors to put money to work – so there needs to be a clear pipeline of investible projects. The government says that it’s ready, pointing to its 10-year strategic infrastructure plan, which includes roads, transport, green energy and digital infrastructure. That’s promising, as long as these projects materialise and become viable opportunities for investors. On the other hand, if not enough projects are available, the initiative can’t work.

Encouraging more investment could be the right move, but there are pros and cons to forcing investors. If government policy succeeds in getting projects off the ground, it could help the country as a whole. It could spur GDP growth and increase the UK’s productivity capacity.

For us as investment strategists, incentives are key if a non-voluntary initiative akin to the Mansion House Accord is to work. If the government wants to attract investment into the UK, there should be incentives here to find a higher return. Those incentives could include tax breaks or subsidies, to increase the returns that pension funds or other long-term investors could earn by investing in the UK rather than elsewhere. Subsidy-type incentives, however, are currently unaffordable to the UK government.

So the government may have to push investors another way, by more regulation rather than incentives. If regulation works, the result could be higher growth and better infrastructure. That’s a potentially large reward for the risk taken – at least in the short term. Nevertheless, the longer-term view must also be noted: too much government repression and co-opting of investments could deter investors, and capital could flee the country as a result. A balanced approach is necessary.

Long-term outlook

Assessing CCLA’s long-term outlook for the UK, one major theme likely to play out is demographics. The UK population is ageing and calls to curb immigration are getting louder. As a result, there could be a natural reduction in the pool of resources available to the UK economy, which may put upward pressure on wages.

That reduction, in turn, could lead to two things: either inflation, which plays itself out in wages and price levels. Or businesses may start to shift capital from hiring labour to investing in automation. Such a shift could be important as business investment has been lacking and raising it is one of the government’s aims.

On one hand, for the government to stimulate investment in capital goods could be seen as a positive. However, it’s important to remember that capital investment is a long-term strategy. Returns take time to materialise, and it could be several years before we reap the benefits.

Immigrants, on the other hand, join the workforce almost immediately, contribute to production right away and pay taxes. The government will have to strike a balance between these two.

Turning to strategic investments: the government has high levels of debt, so it will find it hard to continue to spend. We therefore expect more private-public joint venture initiatives, or at least the environment being created for more private investment houses to come in and invest in Britain. We may even see more foreign money come in.

In the short term, the labour market has been easing, and unemployment is only just starting to rise. Wages are softening, but they still have some way to normalise, which is not unhealthy.

Meanwhile, the UK saving rate (the percentage of GDP that households save every year) has remained over 10% over the last few years, when the long-term average was about 8%. While the lack of consumer confidence could be one cause of this, so are interest rates.

It is likely we are in what some economists call a ‘Wicksellian’ disequilibrium, where the current interest rates favour saving rather than spending. The government would certainly prefer lower bond yields, to better afford its borrowing without the risk of breaking its budget rules.

The Bank of England cutting interest rates could support all three areas.

In the labour market, cutting rates means it’s easier for corporations to meet their debt servicing costs. This makes it less likely that companies need to fire people to maintain their margins, which is supportive of the labour market.

For households, cutting rates can reestablish a Wicksellian equilibrium – a reduction in mortgage and credit card costs can build consumer confidence, reduce the attractiveness of saving products, and push the average household back towards spending.

And for the government, as discussed earlier, a reduction in the Bank of England’s base rate could naturally drag down longer-dated bond yields. This would reduce the government’s borrowing cost and its constant battle to maintain budget headroom.